If You Like Perfect Blue You Will Like

Perfect Blue: A Genre Study

Satoshi Kon is one of the most recognizable names when it comes to anime filmmaking, second only to Hayao Miyazaki. Kon's oeuvre is the darker, grittier, "adult" counterpart to Miyazaki's undeniably charming and more universal appeal. Entering the world of Kon is delving into a kaleidoscopic funhouse of cyber-dreamscapes (Paprika), magical realism (Millennium Actress), and the throes of poverty in modern Japan (Tokyo Godfathers). A versatile artist, Kon deals with distinct subject-matters through a variety of genres. This "genre blending" is common in Kon's films, making them a great source for genre-studying. Perfect Blue (1997) is one such example, where Kon's rich use of genre hybridity weaves a modern tale about the psychological horror wrought by the virtual self.

A Classic Psychological Thriller

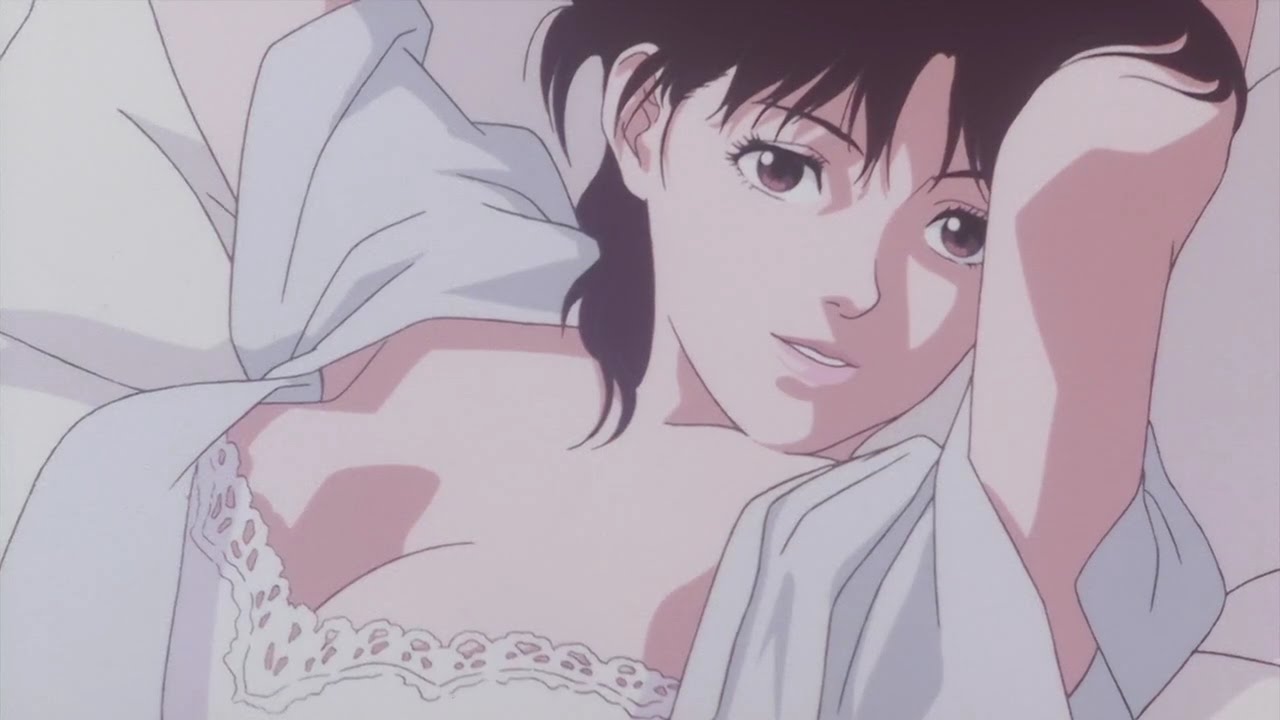

A young pop idol named Mima outrages her fans when she crosses over to "serious acting." This metamorphosis entails an exploitation of her body that does not go over well with her most—disturbingly—loyal fans. Perfect Blue initially presents itself as a psychological thriller, a genre appropriate to the dark theme with which it is principally concerned: the fragmentation of identity in a modern, media-saturated world.

In Perfect Blue, the "thrill" takes the form of Mima-Mania, the protagonist's obsessed fan to whom we're introduced in the film's opening chapter. A concert-venue crew member with a grotesque face (drawn this way to emphasize his monstrosity) stares at Mima with raptured craving during one of her musical performances. It becomes clear to the viewer the only reason this man took this job was to seize the opportunity for physical proximity to a celebrity he worships with unhealthy zeal. Throughout the rest of the film, this proximity will encroach on Mima as Mima-Mania sets out to "rectify" her career move, thereby "killing" (in Mima-Mania's eyes) her former persona.

Following her final performance with her J-pop idol group CHAM!, Mima returns to her (surprisingly) modest apartment where she receives an ominous letter via fax: "I always like looking into Mima's room." This is followed by the now-hackneyed scene of an anonymous phone caller heavy-breathing into the speaker without uttering a single word. In this way, Kon establishes the film's source of haunting eeriness, one in which the viewer, through the subjective perspective of Mima, shares the victim's experience. A perpetual threat is felt in every corner of the urban night, cast by the fluorescent lights which take on a nightmarish form as they provide a false sense of security from inescapable doom (as well as exemplifying the film's "threat of technology" theme, later discussed).

A psychological thriller, as the name suggests, stresses the psychological dimensions of the film. This is done through the exploration of the unstable mental states of its characters, rather than focusing on the process of "catching the bad guy," which has historically belonged to the narrative of the crime genre. Following in the footsteps of Hitchcock's famous precedent Vertigo (1958), Perfect Blue depicts an expression of mental deterioration wherein an ordinary individual, following a traumatic inciting incident, begins to lose their grip on the socially-accepted habitudes of life. In Vertigo, this is Madeleine Elster's pseudo-death from the top of the church bell-tower, prompting a conventionally hardworking detective committed to get the job done to descend into a state of misogynistic, psychological manipulation. Similarly, Perfect Blue begins with a woman who, entering adulthood, is looking to switch gears in her career so as to mature as an artist before getting boxed into her pop-idol image.

A Touch of Teen Horror

This is the familiar venture of many a modern celebrity (think teen stars like Amanda Bynes, Hannah Montana and Lindsey Lohan) who seem to morph into degenerate versions of their "once innocent" selves. In Mima's case, following the traumatic experience of being filmed in a rape scene, her degenerate form takes the shape of a literal "phantom" persona which undermines Mima's ability to discern what is real and what isn't. In both films, the initial use of a crime genre framework is clear, but these function to quickly set up as core conflict the psychological phenomenon with which these films are mainly concerned: exploring the protagonist's fragmented identity.

Mima possesses an adolescent-like naïveté that makes her the perfect subject through whom to explore this phenomenon. From the outset, we see her dressed up in her pink-and-white tutu, evoking grace and innocence, in the middle of a multicolored J-pop trio performing an upbeat song beneath dazzling stage lights. When she returns home and first reads her stalker's "fan-fiction" diary blog, called "Mima's Room," rather than exhibiting the automatic apprehension the viewer expects, she says, in a mildly amused tone, "Somebody sure knows me." Later on, Mima reveals to her managing assistant, Rumi, that she doesn't know how to use a computer. This detail will in particular amuse native Japanese speakers who will have recognized Mima's country accent, thereby combining the "naïve, female protagonist in peril" trope with that of the "starry-eyed country girl embarks on a journey to take on city life" scenario which is so common to Mima's character-type. Mima's arc, then, is a journey of self-discovery in the face of the external forces which threaten to undermine her search for identity.

In light of these observations, Mima's storyline is reminiscent of both "coming of age" teen dramas as well as teen horrors. As Linda Williams explains in Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess:

"…recent teen horror corresponds to a temporal structure which raises the anxiety of not being ready, the problem, in effect, of 'too early!' Some of the most violent and terrifying moments of the horror film genre occur in moments when the female victim meets the psycho-killer-monster unexpectedly, before she is ready"

Williams, Linda. "Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess." Film Quarterly 44 (1991): 2-13.

The "too early" temporality is characteristic of teen dramas, where teenagers have not yet established a stable "adult" identity. Teen years are characterized by a phase of transition, both bodily and psychological. This process is usually complicated through the external forces by which the individual is pressured to adopt an identity they might not be willing to accept and, as such, often find themselves trapped between resistance and an inability to transcend these norms.

In Perfect Blue, these pressures are accepted as a necessary evil. Following the shoot of the rape scene, Mima responds to an interview question: "Of course I would be lying if I said I didn't have any hesitations, but I looked at it as a hurdle I had to jump over as an actress." However, following the episode of the shoot, Mima breaks into tears in the solitude of her room and insists that "Of course I didn't want to do it! But I couldn't trouble all the people who brought me this far!" Although Mima envisions herself embodying a more mature identity, this can only be achieved after having overcome a series of necessary evils. In the teen drama, these are obstacles like: social ostracism, the disillusionment of romance, mindless jobs, and the bureaucracy of higher education. The naïve teenager, then, like Mima, can enter into a new phase of maturity only through disillusion, that is, only once they have been thrust into and overcome a ritual of undesirable hurdles.

Genre-blending to Paint a Modern Allegory in the Age of the Virtual Self

The "horror" elements of Perfect Blue, parceled with its psychological dimensions, tamper with what would have otherwise been the too-early temporality characteristic of the classic "coming of age" teen drama. Just as the film has established itself as a psychological thriller, Kon ceases to follow the activities of Mima-Mania, who we were led to believe would be the film's main antagonist. This is very much not the case, for soon the film has taken a darker turn: overridden by an acute mixture of fear and guilt for the shameful process of exploitation she has condoned, Mima develops multiple personality syndrome.

The growing severity of this condition quickly becomes the film's new primary focus. Mima's spiraling mental state manifests through the "phantom" Mima who bears the characteristics of a ghost, gliding through buildings and hopping on lampposts as a shiny, transparent entity seen only by Mima, the creator of this phantom. Of course, it is inaccurate to attribute "phantom Mima" 's creation as solely Mima's: as we find out at the end of the film, it was Rumi, her middle-aged manager and former CHAM! member, who was behind Mima-Mania and, by extent, Mima's mental deterioration.

Mima's meek naivete means it is only a matter of time before her virtual identity, phantom Mima, has taken over, blurring the line between what is real and what isn't. The viewer experiences these disorienting suspensions of atemporality when the logical link between events becomes muddled. One such moment occurs when Eri, a female character from Double Bind, is explaining that Mima as a pop-idol-turned-actress is only a fictional, self-constructed identity that Mima created as part of the trauma of having been raped. This temporarily leads the viewer to suspect that this, Double Bind, was in fact the reality of the film the entire time—before it is made clear, once we see the studio set, that we were living in a fictional world-within-the-world. This atemporality is characteristic of phantom Mima; after all, what kind of temporality is "virtual temporality"?

By associating this virtual atemporality with severe moments of violence, Perfect Blue combines the psychological thriller and horror genres to remind us of the dangers of letting our virtual identities take control. Sure, it's easy to "freeze" the best moments in our lives and create the semblance of an envy-inducing, exhilarating life. In a media-saturated world, it's even possible to transform oneself into a pseudo-celebrity or an "online personality." But, lest upholding this image should become our life project, it is important to keep a healthy distance away from these superfluous pleasures. Our participation with this atemporality becomes, as with Mima's case, an obsession when it leads to self-absorption, when we have begun to lose focus in fulfilling an authentic life. Mima's case reminds those of us who frequent atemporality (i.e. social networking sites, any site with an "Avatar," etc.) that we are only ever one more "Like" or "Thumbs up" away from becoming our own Rumi, our own Mima-mania—that is, our own downfall to the modern horror-thriller of our lives.

What do you think? Leave a comment.

Receive our weekly newsletter:

Source: https://the-artifice.com/perfect-blue/

0 Response to "If You Like Perfect Blue You Will Like"

Publicar un comentario